Higher Ed Accessibility: An Archival Account of Tuition and Fees at TAMUCC

By: Nicole Edgar

Introduction

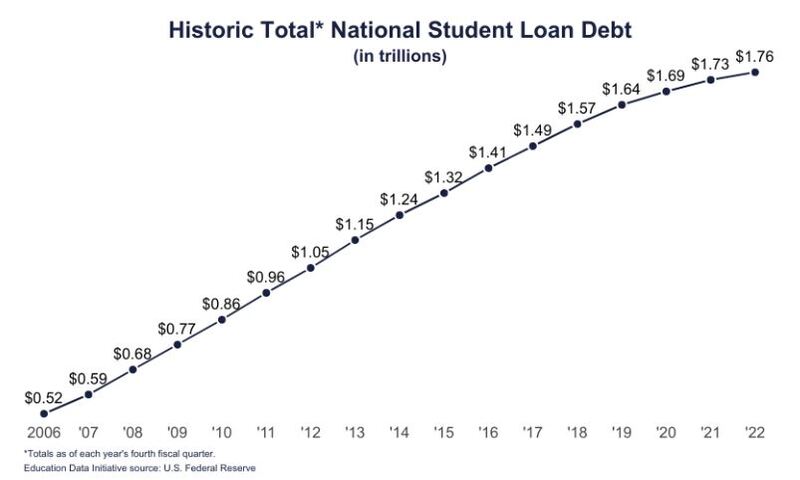

There is no secret that college is expensive. Tuition has steadily increased over the years and in doing so, so too has student borrowing, accounting for the $1.7 trillion student loan debt crisis (Hanson, 2023)[1]. Children and young adults are taught early on in their academic careers that in order to gain upward mobility and economic prosperity that college is necessary. Missing in this conversation, however, is how underpriveledged and minoritized groups will afford inflated tuition prices when already facing economic disparities. Therefore, looking at archival data at TAMUCC has allowed me to see the drastic changes in their cost of attendance from the late 70's to 2023. By analyzing this data, we can see how tuition costs have increased at a higher rate than inflation and how this contributes to the student loan debt crisis - calling into question the accessibility of higher education. In hopes that financial aid practitioners and educational lawmakers take heed in the serious threat that rising tuition prices cause and its contributions to student borrowing, implications are suggested to combat rising costs, reduce student loan borrowing, and pave a way for equitable access to higher education.

Background

Financial aid, a program designed to assist students with tuition costs, began cementing its roots in higher education in 1965 from the Higher Education Act (HEA) by President Lyndon Johnson. Prior to the HEA, student loans were introduced first in 1958 under the National Defense Education Act (later known as the Federal Perkins Loan Program) and only available to a select category of students (New America, 2023)[2]. In 1965 under HEA, this solidified the governments involvement in higher education during the Cold War, and thus began the federal direct loan programs, Federal Pell Grant, and various other grants administered by the government that still act as vital resources for students. David Labaree (2017) mentioned government funding initially being the primary resource for college students, with state appropriations only averaging 25% and oftentimes unreliable (pg. 154)[3]. However, after the Cold War ended, things started to shift between government and higher education. As lawmakers began to slowly back away from an equal balance in loan and grant disbursements, they began instead reducing Pell Grant and increasing federal loans. The goverment's idea, per Labaree (2017), was that college was a great investment for students that ensured future economic prosperity and therefore, students too should shoulder the cost[4]. This fractured mindset is what began and continues to be attributed to the student loan debt crisis. Furthermore, tuition prices around the world continue to skyrocket. More and more students are left with high tuition bills, resulting in more borrowing. Current data reflects total national student loan debt is $1.7 trillion with an upward trend (Hanson, 2023)[5]. This, and other facets, has sparked the interest in analyzing archival tuition and fee data at TAMUCC while considering the implications for student borrowing. If government and state spending continues to decline, with state appropriations expected to be zero by 2059 (Labaree, 2017), this, too, calls into question the accessibility of higher education (pg. 156)[6].

Analysis

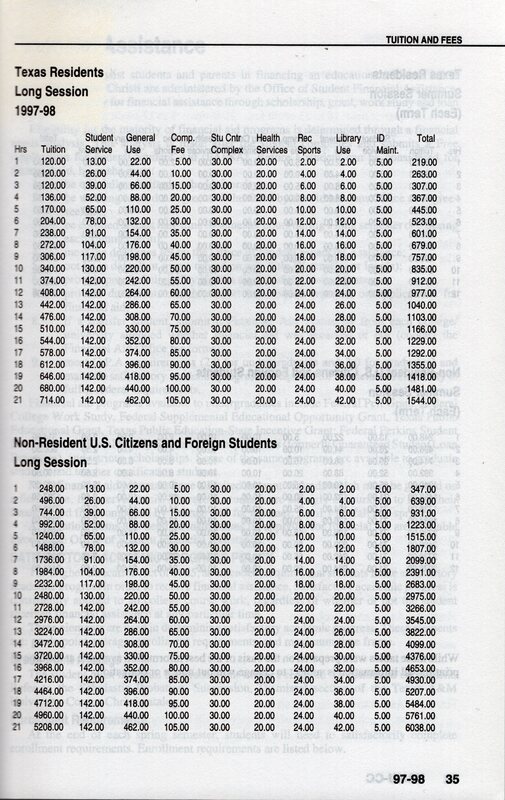

The archives at TAMUCC contained a multitude of information relating to financial aid resources and tuition costs than spanned throughout decades. In this 1997-1998 TAMUCC student handbook, we can see a full-time Texas resident student attending TAMUCC (formerly CCSU) can expect a tuition bill of approximately $977.00 per term (TAMUCC, Course Catalog, 1997)[7]. For full-time non-resident students, the cost is quadrupled to a whopping $3,545.00 per term. Institutions charge higher out of-state tuition due to non-resident students’ not having paid state tax dollars. Also, out of state tuition brings in more revenue that is used for multiple purposes. During this time, the average cost of attendance to attend TAMUCC was $5,259 and the average total indebtedness per-borrower was $9,642 (TAMUCC, 2023)[8].

Government funding during this time was also generous, with its Federal Pell Grant Program nearly paying 100% of a students’ total tuition bill with minimal borrowing. In 1997, American student debt reached approximately $41 million (now $1.7 trillion) with the majority of loans stemming from private institutions (Baum, 2013)[9]. At TAMUCC, however, student borrowing was minimal with government and state appropriations assisting with need-based aid. Now, fast forward to 2023-2024 where institutions are fighting to survive, inflation has impacted nearly every American, tuition costs have skyrocketed, and government and state funding is gradually declining. This, amongst other facets, begs the question: how has access to higher education changed from the late 90’s to now?

In this 2023-2024 TAMUCC tuition table, a full-time Texas resident student pursuing a degree in education, liberal arts, science, or the arts can expect a tuition bill of approximately $4,641.00 per term[10]. Long gone are the days where the Federal Pell Grant covers a full tuition bill (you’re lucky if it covers a fraction now), with students having to rely on other sources of aid to shoulder the cost, and oftentimes, out of pocket. Let’s look at some staggering facts:

- The average federal student loan debt is now $37,338 per borrower (Hanson, 2023)[11].

- The average cost of attendance in 2023-2024 for a full-time Texas resident at TAMUCC is approximately $25,000 per academic year (TAMUCC, 2023)[12].

- The average federal student loan debt for TAMUCC students is $23,000 (Usnews, 2023)[13].

- Private student loan debt averages $54,921 per borrower (Hanson, 2023)[14].

- Americans own $1.7 trillion in federal and private student loan debt (Hanson, 2023)[15].

Furthermore, inflation has skyrocketed, leaving universities (including TAMUCC) no choice but to increase tuition prices in order to survive with no clear end in sight. Labaree also (2017) mentioned higher educations need for prestige by arguing, “American colleges need to be able to compete successfully with their peers to attract students, and they also need to make the college experience so compelling and personally formative that graduates will maintain a deep, lifelong loyalty to the institution” (pg.184)[16]. This chase for prestige contributes to increased tuition prices by showing the value of their education and institution. Additionally, financial aid packages are becoming more and more unfavorable, not accounting for inflation and student loans being the primary offers. The Department of Education’s formula to determine a student’s EFC (Estimated Family Contribution) continues to stain funding access by calculating how much they think a family can afford out of pocket while scholarships continue to be awarded on a meritorious basis. The question, then, is how are higher education institutions ensuring equitable access for all demographics? In 2021, TAMUCC met only 64% of its students financial aid need with student and parent loans auto-populated in financial aid packages (Usnews, 2023) [17].

If tuition continues to be increased with financial aid not accounting for all students' financial need, how, then, does this affect student borrowing? The answer is unfortunately quite simple - they borrow more.

Implications

In reviewing archival data spanning from the late 70’s to now, 2023, some implications for TAMUCC can be made for financial aid practitioners and educational lawmakers to reduce student borrowing and increase student access to higher education:

- Limit financial aid packages to exclude loans. Colleges should have a civic responsibility for loan borrowing. Williams (2006) argued that loans as an emergency resource is not a bad arrangement but should not stipulate the majority of funding options[18]. In my professional career as a financial aid administrator for over 7 years, students run into the issue of “over borrowing” instead of borrowing only what is needed. Therefore, by excluding loans altogether, this forces the students to meet with a professional who can advise them appropriately if a loan is in fact needed.

- Financial aid literacy education. A huge indicator of over borrowing is a lack of financial literacy. When students do not have basic financial concepts, they make poor financial decisions that can have lasting impacts. By incorporating financial literacy into higher education institutions, this could potentially reduce student borrowing by giving the students the tools they need to make financially well decisions.

- Reduce tuition costs. This is easier said than done as universities have virtually turned into microcosms – relying on donor’s, students, athletics, and appropriations to make ends meet. And as universities continue to grow, so too will tuition. But by reducing tuition costs, this will potentially force universities to be more strategic in budgeting and could eliminate inessential expenses.

- Increase funding. Per Pew Trust (2019), higher education is overall a small part of federal spending, with only 2% accounting for major higher education programs[19]. Educational lawmakers could increase government support by re-analyzing expendintures and placing more assistance into educational pools. With an increase in government spending for higher education programs, this could also potentially reduce poverty rates and welfare assistance.

- Shift the lending responsibility to universities. Williams (2006) mentioned retaining the basic structure of student loans but putting the responsibility in the hands of the universities instead of the government and banks[20].

- Make state appropriations go directly to tuition bills. Currently, most state appropriations go towards non-academic related expenditures including maintaining facilities and institutional operations. By ensuring state aid goes directly to the student, this could force institutions to re-think budgeting strategies and cut out unnecessary spending.

Conclusion

The impact high tuition prices have on students is astonishing. Students and parents are having to borrow more as a result of a faulty system that views education as a mere business. Higher education institutions lack accountability measures for student borrowing as they fail to acknowledge the long term effects of debt. Williams (2006) argued in his personal narrative the lasting impacts of debt (choosing to go to the doctor or not with a minor illness) and questions the validity of the American dream (pg. 156)[21]. Financial aid practioners and educational lawmakers must come together to tackle student borrowing and eliminate the threat it poses post-graduation. Universities must also reduce the microcosm's they have created and get back to academic rigor and student success.

References

[9]Baum, S. (2013). The Evolution of Student Debt in the US. The Urban Institute. https://www.upjohn.org/stuloanconf/Baum.pdf

[3] [4] [6] [16]Labaree, D. F. (2017). A perfect mess: The unlikely ascendancy of American higher education. University of Chicago Press.

[1] [5] [11] [14] [15]Hanson, M. (2023). Student Loan Debt Statistics. Education Data Initiative. https://educationdata.org/student-loan-debt-statistics#:~:text=20%25%20of%20all%20American%20adults,debt%20growth%20rate%20is%2015%25.

[2]New America. (2023). The Higher Education Act of 1965. New America. https://www.newamerica.org/education-policy/reports/higher-education-act-1965/introduction/

[19]Pew Trust. (2019, October). Two Decades of Change in Federal and State Higher Education Funding

[7]TAMUCC, Course Catalog, 1997

[10] [12]TAMUCC. (2023). FY2024 Cohorts Fall & Spring Tuition Table. https://www.tamucc.edu/finance-and-administration/financial-services/business-office/tuition-and-fees/charts-tuition-fees/assets/documents/fall23spring24/fy24_gtp_f23_s24_aoc.pdf

[8]Texas A&M University Corpus Christi. (2023). Common Data Sets. TAMUCC.edu. https://www.tamucc.edu/president/pir/common_data_set.php

[13] [17]U.S.News. (2023). Texas A&M University - Corpus Christi Tuition & Financial Aid. https://www.usnews.com/best-colleges/texas-am-university-corpus-christi-11161/paying

[18] [20] [21]Williams, J. (2006). The pedagogy of debt. College Literature, 33(4), 155-169. doi:10.1353/lit.2006.0062