Pearl Harbor: "Japanese vs. American Civilian Perspectives"

American vs. Japanese Civilian Perspectives

American and Japanese civilians had very opposite reactions following the events of December 7th, 1941. For American citizens, Pearl Harbor represented “A Day Which Will Live in Infamy.” For citizens of Japan, Pearl Harbor represented the success of a justified military retaliation. Civilians from both nations were naturally predisposed to sympathize with their individual country's interpretation of the event. This phenomenon is a typical feature in national conflicts, but was exacerbated following Pearl Harbor due to elements of “nationalism” – a sense of loyalty to one’s own nation; patriotism. The American and Japanese governments both utilized nationalism to their advantage, and implemented various forms of propaganda as tools for shaping their civilians’ perspectives. In the case of Pearl Harbor, the concept of “national superiority” prevented civilians on both sides of the conflict from considering the merits of their opponent’s perspective.

Japan

Japanese civilians were more likely to view the actions of Pearl Harbor as a justified reaction to the economic embargo by western countries. Not only were the Japanese more aware of the embargo’s existence, but they were also more likely to view the action as the critical point of American hostility. In response to Japan’s Imperial expansion in the East, The United States (along with Britain and the Netherlands) froze Japanese assets within America. This embargo included the majority of Japan’s oil supply, backing the nation into a corner economically.

Japanese civilian perspective were additionally shaped by their extreme nationalist culture, and utilization of militaristic colonialism as an economic stimulant. Japanese leadership viewed the West’s condemnation of Japanese occupation as hypocritical, particularly in light of America’s own occupation within Asia (6.) Japanese national extremism arose from their complex ancient heritage, along with a culturally engrained xenophobia (hatred of the foreign). This xenophobia manifested itself even in attitudes toward people in the Asian territories occupied by Japan. The horrific action of forcing over 200,000 women, 90% Korean, into a military sanctioned prostitution program of “comfort women,” is just one example of xenophobic influence.(3.)

In additional to elements of nationalism, the perceived insult of the United States trade embargo resulted in Japanese civilians’ view of Pearl Harbor as justified. By 1940, Japan found its fuel and ammunition resources to be severely depleted.(4.) America was an emerging new star within the oil-industry, serving as Japan’s primary resource for fuel. American and Japanese relations had been on a steady decline, ever since the Japanese expansion during “Manchurian Incident” of 1933 (an excuse for the Japanese to invade Manchuria).(4.) In July 1940, passage of the “Export Control Act” provided President Roosevelt with the means to retaliate against Japanese expansionism.(4.) Japan attempted diplomatic resolution to the embargo on several occasions, to which America was unwilling to make any concessions. Japanese citizens were enraged with America’s negative reaction to attempts at diplomacy. Itabashi Koshu, was a Japanese middle-school student during the Pearl Harbor attacks. He describes the experience in his Oral History entitled, "My Blood Boiled at the News":

“The Americans, British, Chinese, and Dutch; they wouldn’t give us a drop of oil! The Japanese had to take a chance. That was the psychological situation in which we found ourselves. If you bully a person, you should give him room to flee. There is a Japanese proverb that says, ‘A cornered mouse will bite a cat.’ America is evil, Britain is wrong, we thought. We didn’t know why they were encircling us.”(2.)

This passage highlights the general sentiments of the Japanese public. The average Japanese citizen viewed the actions of the American embargo and refusal to negotiate as the behavior of a bully. From their perspective, America had trapped Japan and left the country without the ability to flee the situation. The Japanese proverb referenced by Koshu, is a perfect example of how many Japanese citizens interpreted their bombing of Pearl Harbor: “A cornered mouse will bite a cat!”(2.)

America

American civilians in general were unaware of their government’s embargo of Japanese assets. Therefore, they were more likely to view the actions of Pearl Harbor as an unprovoked sneak attack. For Americans, Pearl Harbor also had the effect of unifying the populace around a national identity. Pearl Harbor, was the first and only attack on the United States homeland during World War 2.

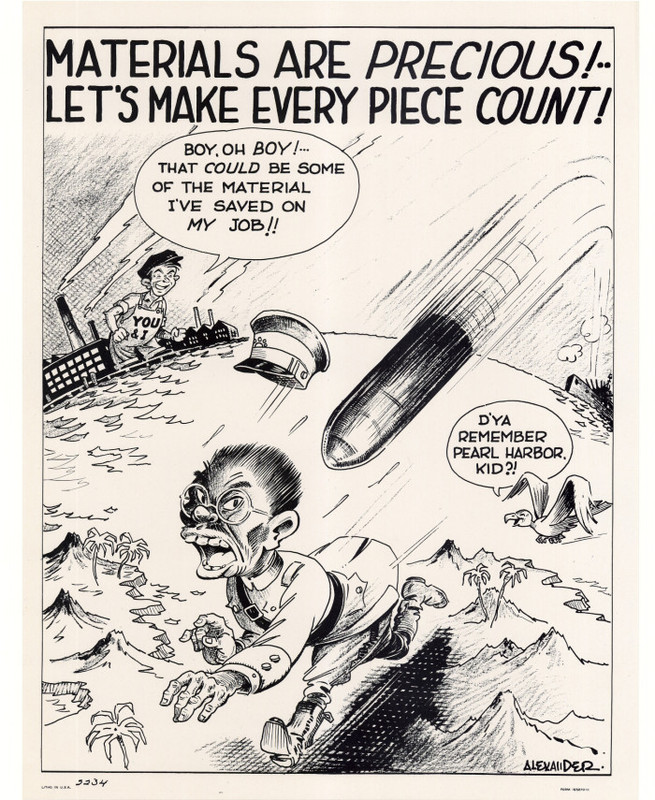

Japanese kamikaze attacks added an additional element of fear for the American populace, as seen in the propaganda piece “Materials are precious! --let's make every piece count!”.(1.) This American propaganda poster (displayed on the frame to the left) exemplifies the perspective pushed by the United States upon its citizens. The poster features an American aircraft carrier shooting a missile at a running Hideki Tojo caricature, while a nearby seagull exclaims: “Do ya remember Pearl Harbor now kid?!” (1.)

The underlying purpose of this poster is to persuade American citizens to donate materials for the war effort. This is accomplished by drawing on Americans’ outrage over the perceived preemptive nature of the Pearl Harbor attack. In the top-left corner of the poster, an American citizen expresses his satisfaction that his donation might be used to eliminate Tojo.

Before Pearl Harbor, Americans remained largely indifferent towards the war. That attitude changed after the events of December 7th, 1941. Like the exclamation “Remember the Alamo!” before it, “Remember Pearl Harbor!” was used to rally public support for the war. This is why Franklin D. Roosevelt obsessed over fine-tuning his response to the attack, writing three drafts of his speech before the next day.(5.) Roosevelt seemed preoccupied in his edits, emphasizing a false-account regarding the unexpected nature of the attack: “A few words later, he changed his report that the United States of America was ‘simultaneously and deliberately attacked’ to ‘suddenly and deliberately attacked.’ At the end of the first sentence, he wrote the words, ‘without warning,’ but later crossed them out.”(5.)

Conclusion

Making the Japanese attack appear random and unprovoked was an issue of extreme importance to Roosevelt and his government. American officials sought to portray themselves as completely unaware, victims of an unpredictable act of Japanese violence. The notion that the United States government was unaware of Japan’s incoming attack, falls apart under the microscope of historical scrutiny. Historians Paul S. Burtness and Warren Ober, describe the extent of the government’s involvement in “Provocation and Angst”, saying that: “Washington had sent repeated alerts to all the Pacific bases—indeed, FDR had personally ordered warnings sent on November 27 and 28, which included a note that in a confrontation, the United States would prefer to have the enemy fire first.”(7.)

Roosevelt and a small circle of advisors had been following Japanese policy through radio intercepts.(8.) Incriminating coded messages had been translated by American cryptographers, and were delivered to the Secretary of State prior to the attack.(8.) Though American intelligence did not know the precise location of the attack, they knew of Japan’s plan for military retaliation in the event negotiations broke down.(8.) These factors serve as a reminder for individuals, and American citizens in particular, not to accept any given statement at face value. For an individual to benefit from the Historical discipline, they must be willing to acknowledge the bias present within every source, including their own country.

Bibliography:

-

Alexander. “Materials are precious! --let's make every piece count!” University of North Texas Libraries, Digital Library, digital.library.unt.edu; crediting UNT Libraries Government Documents Department.

-

Koshu, Itabashi. “My Blood Boiled at the News” Japan at War an Oral History. Transcript of an oral History by Haruko Cook and Theodore Cook, The New York London Press, pg.77

-

Howard, Keith. “True Stories of the Korean Comfort Women” Cassell. London, 1995. Pg. V

-

Kennedy, Ross A. "Strategic Calculations in Woodrow Wilson’s Neutrality Policy 1914–1917", The Journal of the Gilded Age and Progressive Era 17, no. 4 (2018)

-

"Crafting a Call to Arms: FDR's Day of Infamy Speech", National Archives and Records Administration. Accessed November 20, 2018.

-

Mueller, John. “Pearl Harbor: Military Inconvenience, Political Disaster”, International Security, MIT Press. Vol 16, no.3 (1991) Pg. 172-203

-

Burtness, Paul. Warren, Ober. “Provocation and Angst: FDR, Japan, Pearl Harbor, and the Entry into War in the Pacific.” Hawaiian Journal of History, vol 51, November (2017) Pg. 91–114.

-

Maechling, Charles. “Pearl Harbor: The First Energy War”, History Today, vol 50, no. 12, December (2000) Pg. 41

Oral History

Koshu, Itabashi. "My Blood Boiled at the News", Japan at War an Oral History. Transcript of an Oral History by Haruko Cook and Theodore Cook, The New York London Press. Pg. 77-78

This Oral History is a primary account of Itabishi Koshu's experience as a Japanese middle-school student, at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack. The account describes the elation of the Japanese populace, after finding out about the bombing: "The whole nation bubbled over, excited and inspired. 'We really did it! Incredible! Wonderful!' That's the way it felt then."

Itabishi also addresses the issue of Japanese nationalism, and says of the environment: "I was brought up in a time when nobody criticized Japan."

The extremely nationalist Japanese society, created an environment where pride negatively impacted leadership decision making. Itabishi describes: "'Withdraw your forces,' America ordered Japan. If a prime minister with fore-sight had ordered a withdrawal, he probably would have been assassinated. Even I knew that withdrawal was impossible!"

He goes onto describe how the events of "Pearl Harbor" influenced his decision to join the military. This is very much an example of the effects of ultra-nationalism, upon the Japanese civilian disposition.